By Alessa Wylie

Ellen Louise Payson (1894-1977) known to family, friends and clients as Louise, is considered a pioneer of American landscape architecture. She gained widespread recognition during the 1920s and '30s as an accomplished landscape architect “for the soundness with which she applies to her gardens the principles of landscaping and architecture … and for the sympathetic feeling for varying material which her work always shows.”

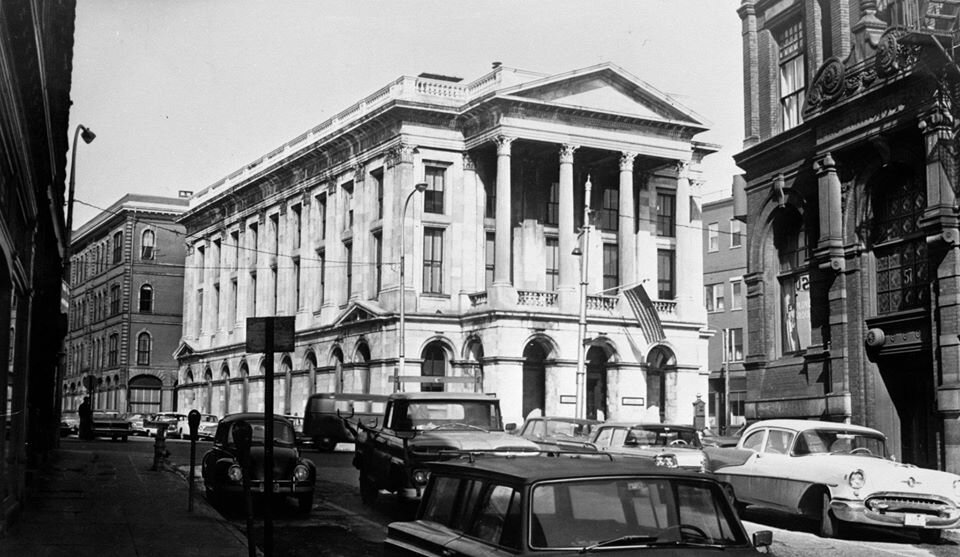

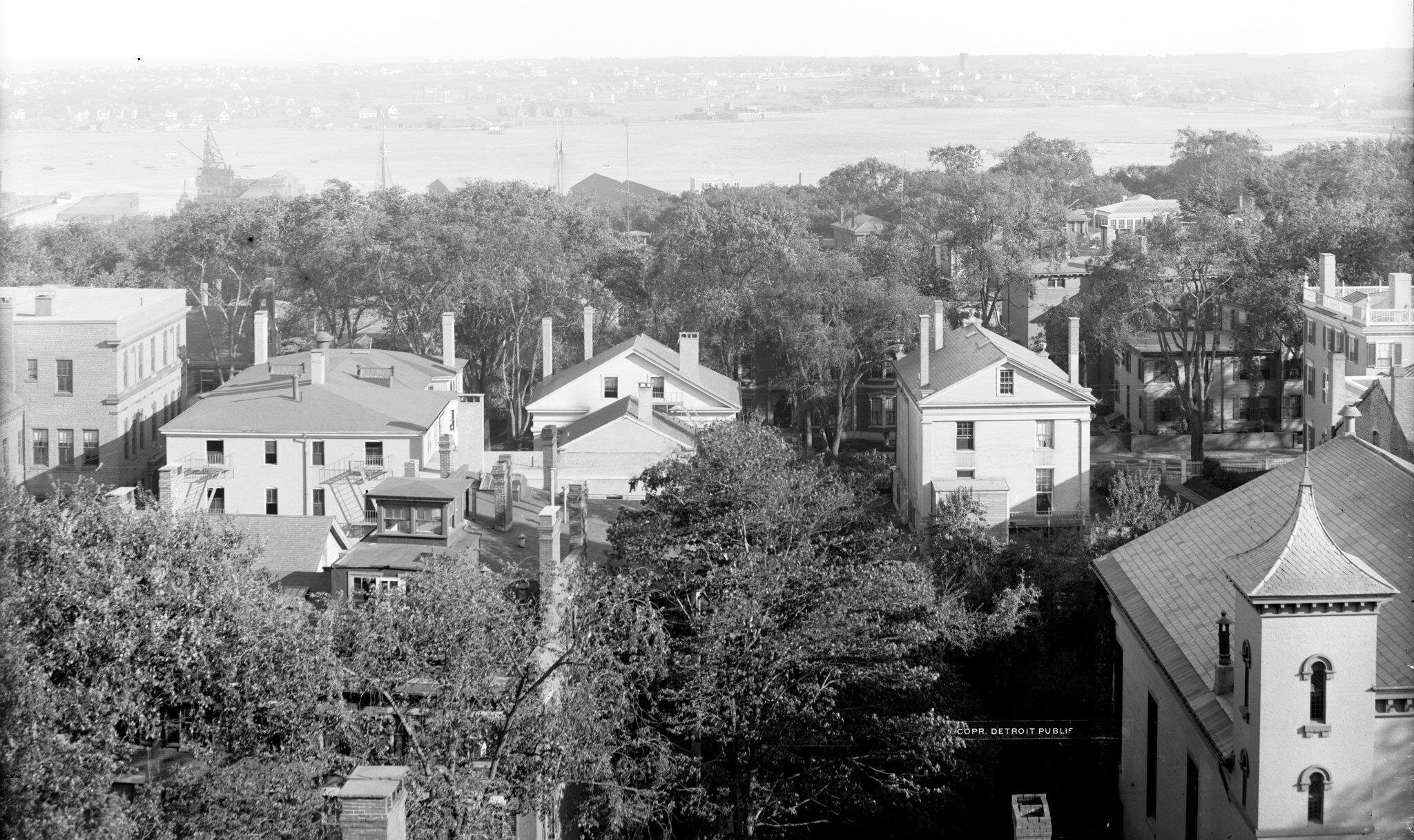

Louise Payson was born in Portland, Maine, the daughter of Edgar Robinson Payson and Harriet Estabrook Payson of the prominent Payson family. She was four years old when her mother died of typhoid fever and her father’s sister Jeannette came to live with the family. Aunt Jeannette and her close friend and companion, Annie Oakes Huntington would play an important role in Louise’s life. Aunt Jeannette loved to travel and Annie Oakes Huntington was a well-known botany expert whose 1902 book Studies of Trees in Winter was so successful it was reprinted three times and used as a textbook at the Yale School of Forestry. These two women greatly influenced Louise throughout the years.

Cover of a 1920s brochure for the Lowthorpe School

Payson attended the Lowthrope School of Landscape Architecture, Gardening and Horticulture for Women in Groton, Massachusetts. It was the only landscape architecture program available for women in the United States at the time. Students studied architecture and landscape history, drawing, drafting, surveying and site engineering, principles of construction, along with plant material, forestry, botany, and entomology. The school was located on a 17-acre estate that included a fruit orchard, flower and vegetable gardens, meadow and pastureland and a small arboretum of trees and shrubs that provided a place for plenty of practical, hands-on experience.

Louise Payson graduated from the Lowthrope School in 1916 and went to work for landscape architect Ellen Shipman. Shipman had started her business in New Hampshire in 1912 and eventually expanded to open an office in New York City. She only employed women and provided professional opportunities that allowed many of them to set up successful practices of their own like Louise Payson did in 1927. Shipman wrote “Louise Payson came fresh from Lowthorpe, so young and full of ability, and after twelve years with me, started out brilliantly for herself.”

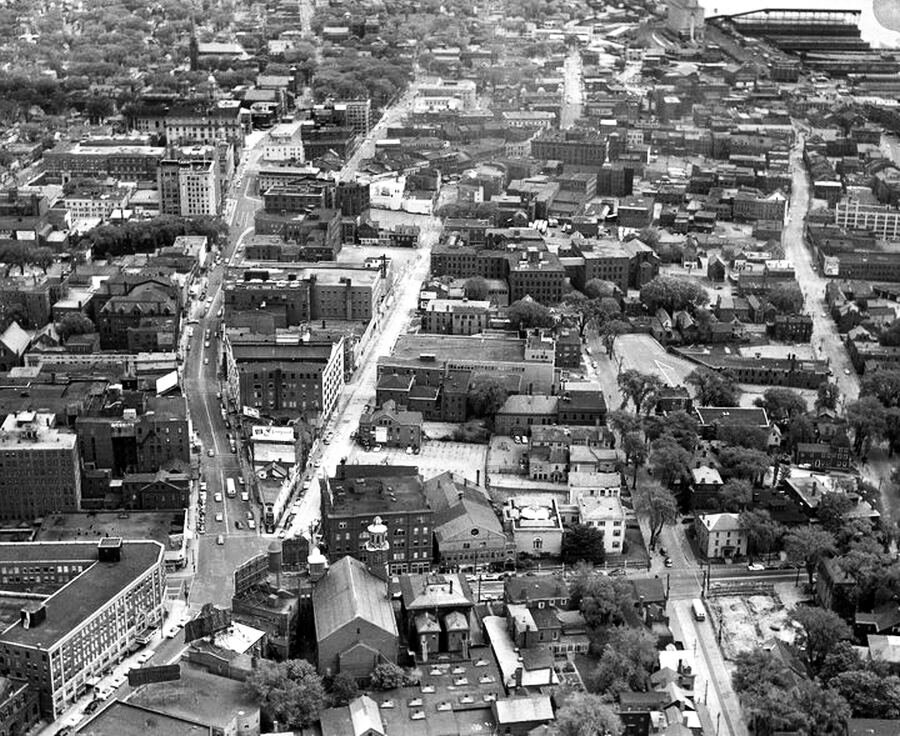

In the beginning of Louise’s career, she created landscape plans for family members in Portland’s Western Prom neighborhood and in Falmouth Foreside. The earliest known surviving drawing is a design for her father at 83 Carroll Street in 1917. The house was a semi-detached residence designed by local architect George Burnham (the subject of last week’s architect spotlight.) The Payson’s lived in the eastern half on the corner of Carroll and Chadwick Streets. To create the gardens Louise used a variety of small-scale shrubbery showing not only her knowledge of plants but also her understanding of the size of the yard.

Planting plan for E.R. Payson, Portland

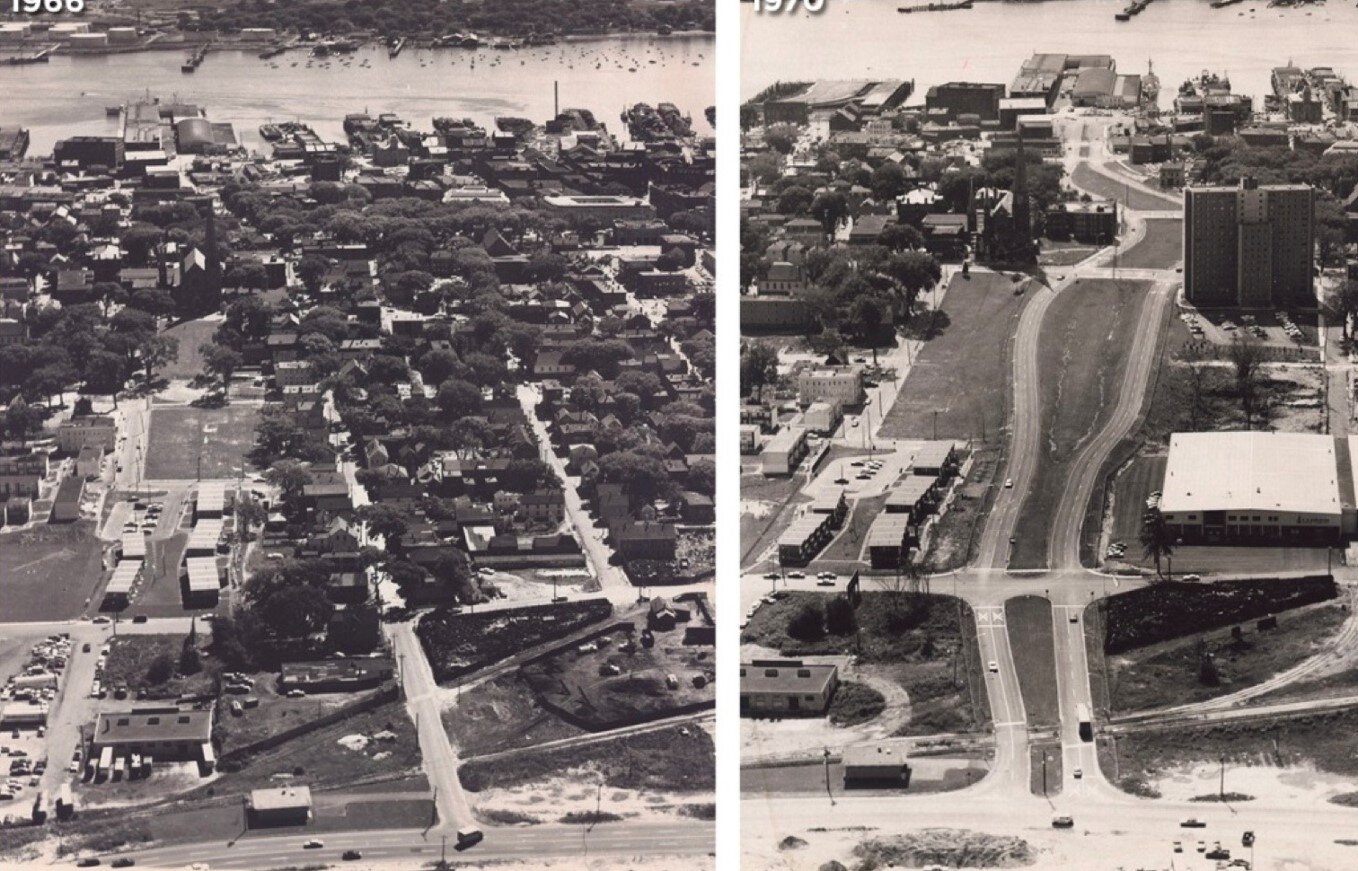

That same year Louise also designed a 33 by 70-foot perennial garden for her Uncle Charles in Falmouth Foreside choosing plants that she would continue to use throughout her career. Additionally, many of Louise’s drawings include maintenance information. “Very important for the success of the garden is the careful staking. The plants much not be tied to the stakes, but the stakes placed around the plant or group of plants of the same variety, and raffia tied to the stakes leaving the plants free in the center.”

Enclosed perennial garden for Charles Payson, Falmouth Foreside

Cumberland Foreside heart-shaped garden

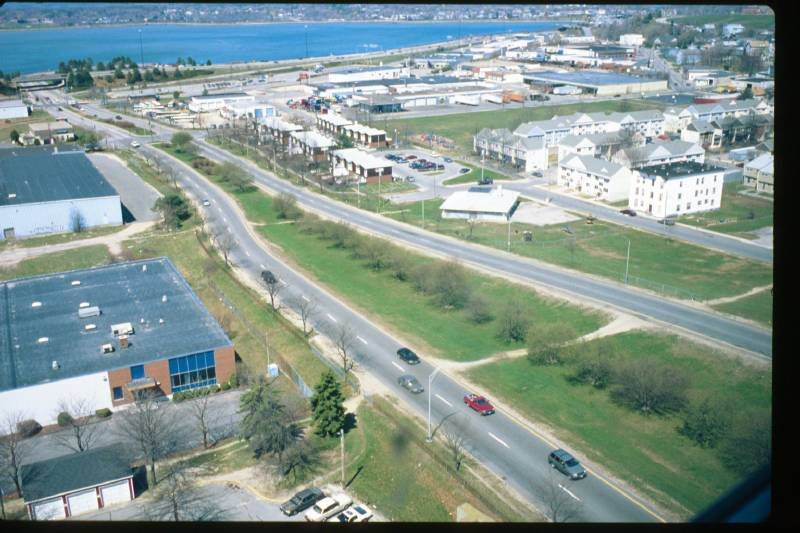

Louise Payson left Ellen Shipman’s office in 1927 and started her own practice in New York City, where she followed Shipman’s practice of hiring only women. She maintained her office from 1927 through 1941 and completed over seventy commissions, designing the grounds of several large estates in Connecticut and New York, including the estate of her cousin Charles S. Payson. Her smaller projects included a hidden, heart-shaped garden for her cousin in Cumberland Foreside as well as other gardens in New England, New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania and as far west as Missouri.

Although there was a great range in the scale of her projects, there was a consistency and symmetry in her designs that also reflected her extensive knowledge of plant material and her engineering ability. In addition, she designed fences, buildings, and trellises with a sensitivity to the architectural style of the residence.

In 1931 Payson joined the American Society of Landscape Architects (ASLA) and her design for the John P. Kane Estate in Locust Valley, NY was included in the 1934 Yearbook of Members Work and several other of her projects from this period were published in House Beautiful, House and Garden and Home and Field.

Judith B. Oliver (seated) in her Ogunquit garden designed by Lousie Payson

House and Garden also selected a Louise Payson-designed landscape in their 1933 “Little House” competition. The idea was to inspire readers of the possibilities for their own dream house with an imagined site that was a corner suburban lot, 60 by 150 feet. Architects designed a small Georgian house with French influences and Louise’s design divided the lot into five areas to utilize all the available space.

Despite the Great Depression, Louise continued to receive commissions throughout the Northeast. They varied tremendously in scale and type from large estates to roof-top gardens in Manhattan. She closed her office in June 1941 and as U.S. involvement in World War II intensified, she worked at Eastern Aircraft in Pennsylvania to support the war effort. In 1944 she sailed to Portugal to volunteer in Lisbon as a relief worker.

When she returned 17 months later, she didn’t open an office but she did continue to design gardens mostly for family and friends. She also didn’t charge them, instead she asked that a donation be made to one of her favorite organizations including the National Society of Colonial Dames of America in the State of Maine, The Victoria Society of Maine, The Longfellow Garden Club, and the Maine Audubon Society.

In 1951 she purchased a farm in Windham and planted extensive gardens, dividing her time between the farm and her Portland home. She remained active in various organizations and traveled extensively. She died unexpectedly in 1977 at the age of 82 while on a Mediterranean cruise.

As a woman practicing in what historically had been a male-dominated field, Louise Payson helped redefine the character and qualities that established the distinctiveness of American gardens and estates during what is know as the “Golden Era of American Landscape Architecture.”

Shortly after her death family members discovered a sizable collection of original plans, drawings and other works stored in a large chest at a family home in Portland and in 1999 donated the collection to the University of Maine.

The collection contains about 525 architectural drawings including landscape architecture plans, contour drawings, planting diagrams and blueprints. The index to the collection can be found at https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/findingaids/299. The Special Collections, Raymond H. Fogler Library, University of Maine, "Payson (Ellen Louise) Collection of Landscape Architectural Drawings, 1913-1941" (2016). Finding Aids. Number 299.