67 High Street's Remarkable Journey

Tucked between two imposing structures on High Street sits a remarkable little house that catches the eye of anyone passing by. Number 67 is notable for its diminutive size and surprisingly rich architectural character—a double-height bay window, a delicate oculus, and a tiny balcony perched above the front door. Set back from the street, this modest brick dwelling tells an unusual story of transformation and craft.

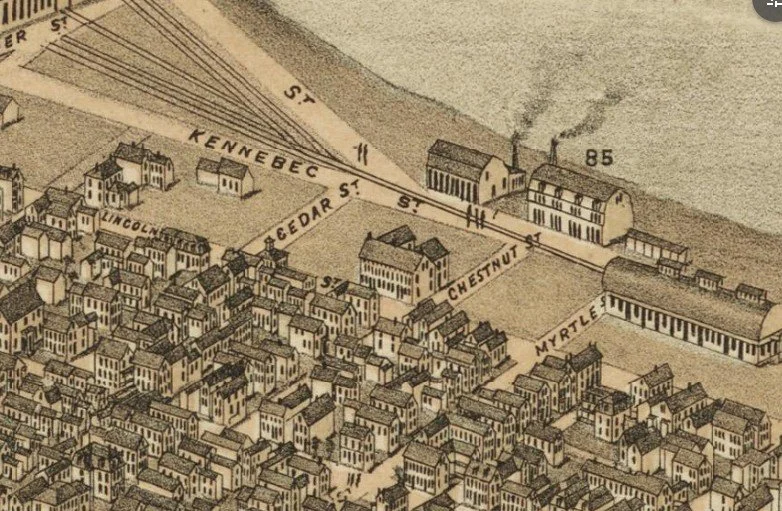

The building's origins are humble. Between 1877 and 1882, Portland Savings Bank constructed a simple rectangular brick barn on this lot, likely to service the large 1799 house next door at 69 High Street. The two-story structure with multiple windows probably functioned as a carriage house or stable, its sturdy brick construction built to last.

In 1892, prominent Portland carpenter and contractor Spencer Rogers purchased the property from the bank. Rogers and his family lived next door at number 69, and for over a decade, the brick barn remained a utilitarian outbuilding. Sometime before 1904, the Rogers family saw potential in those solid brick walls.

By 1904, Spencer Rogers' will mentioned "two houses" at 67 and 69 High Street, and city directories began listing number 67 as a residence. The transformation was complete by 1909, when fire insurance maps showed a two-story brick dwelling with its distinctive angular front bay. The barn had become a home.

Upon Spencer's death in 1904, the property passed to his son Edward, and eventually to Edward's wife Hattie in 1915. The Rogers family, who were all experienced carpenters, had turned a humble stable into a showpiece. The prominent bay window, decorative oculus windows, and ornamental cap over the entrance weren't just charming details; they were advertisements for Rogers and Son's craftsmanship.

Throughout the early twentieth century, the little house served the family well, alternately rented out and occupied by various Rogers family members, including Edward and Hattie's son Everett and his wife Nellie. Today, this converted carriage house remains a beloved architectural curiosity—proof that skilled hands, creative vision, and solid brick construction can transform the ordinary into something extraordinary.

GPL wishes to thank Kate Bourne and Mark Munger for their interest in this history, stewardship of the building, and inviting us to visit and learn more about the property!