A site in Portland was included in The Negro Travelers’ Green Book, a well-known guidebook for African Americans travelling in the mid-twentieth century.

The St. John Valley neighborhood began to develop around Portland’s Union Station in the late-19th century as people were employed by the railroad industry and became home to a Black community in the early twentieth century. The railroad was a hub of employment for Black Portlanders who worked as Red Caps, food vendors, and matrons.

Benjamin Thomas worked as a Red Cap at Union Station while his wife Edie and other family members operated the Thomas House Tourist Home, a 16-room roomA site in Portland was included in The Negro Travelers’ Green Book, a well-known guidebook for African Americans travelling in the mid-twentieth century.

The St. John Valley neighborhood began to develop around Portland’s Union Station in the late-19th century as people were employed by the railroad industry and became home to a Black community in the early twentieth century. The railroad was a hub of employment for Black Portlanders who worked as Red Caps, food vendors, and matrons.

Benjamin Thomas worked as a Red Cap at Union Station while his wife Edie and other family members operated the Thomas House Tourist Home, a 16-room rooming house nearby at 28 A Street. Owing to the green lantern, lit rain or shine, underneath the front bay window the business was more commonly known by its nickname “The Green Lantern”. This site was featured in a great Boston Globe piece,"When travel was treacherous for Black people: The Green Book’s legacy in New England,“ last weekend, for which Greater Portland Landmarks provided research and an interview.

Edie Thomas had a contract with the government in WWII to feed soldiers, and the café on the first floor, known as the Green Lantern Grill, was a place where Black soldiers and sailors could join trainmen, chefs, and others to play cards and listen to music. It was a lively social gathering space for the Black community in the1940s and 50s.

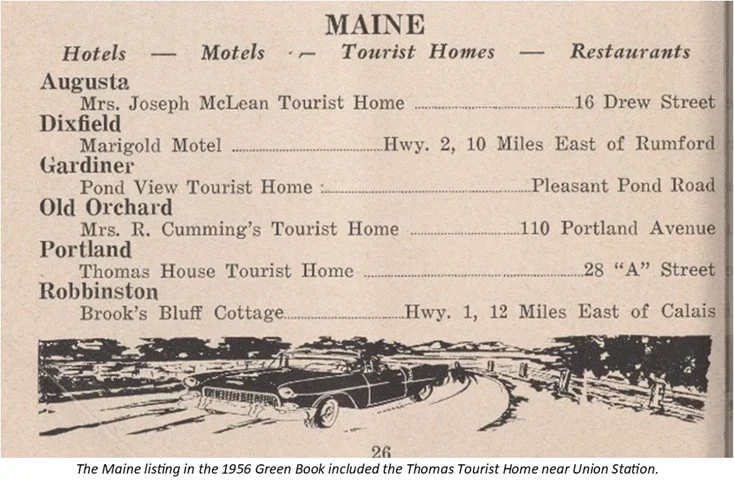

The Thomas House Tourist Home was listed in the Green Book, a guidebook for African American roadtrippers as a safe place for a meal and rest. The Green Book was originated and published by New York City mailman Victor Hugo Green from 1936 to 1966, during the era of Jim Crow laws, when open and pervasive racial discrimination against Black people meant they faced a variety of dangers and inconveniences along the road, from refusal of food and lodging to arbitrary arrest. In response, Green wrote his guide to services and places relatively friendly to African Americans, eventually expanding its coverage from the New York area to much of North America, as well as founding a travel agency.

The original house no longer stands, but the site is an important reminder of Portland’s Black community in the early 20th century, their significant contributions to the transportation industry and the history of Union Station, the discrimination they faced, and a special place of welcome.ing house nearby at 28 A Street. Owing to the green lantern, lit rain or shine, underneath the front bay window the business was more commonly known by its nickname “The Green Lantern”. This site was featured in a great Boston Globe piece,"When travel was treacherous for Black people: The Green Book’s legacy in New England,“ last weekend, for which Greater Portland Landmarks provided research and an interview.

Edie Thomas had a contract with the government in WWII to feed soldiers, and the café on the first floor, known as the Green Lantern Grill, was a place where Black soldiers and sailors could join trainmen, chefs, and others to play cards and listen to music. It was a lively social gathering space for the Black community in the1940s and 50s.

The Thomas House Tourist Home was listed in the Green Book, a guidebook for African American roadtrippers as a safe place for a meal and rest. The Green Book was originated and published by New York City mailman Victor Hugo Green from 1936 to 1966, during the era of Jim Crow laws, when open and pervasive racial discrimination against Black people meant they faced a variety of dangers and inconveniences along the road, from refusal of food and lodging to arbitrary arrest. In response, Green wrote his guide to services and places relatively friendly to African Americans, eventually expanding its coverage from the New York area to much of North America, as well as founding a travel agency.

The original house no longer stands, but the site is an important reminder of Portland’s Black community in the early 20th century, their significant contributions to the transportation industry and the history of Union Station, the discrimination they faced, and a special place of welcome.