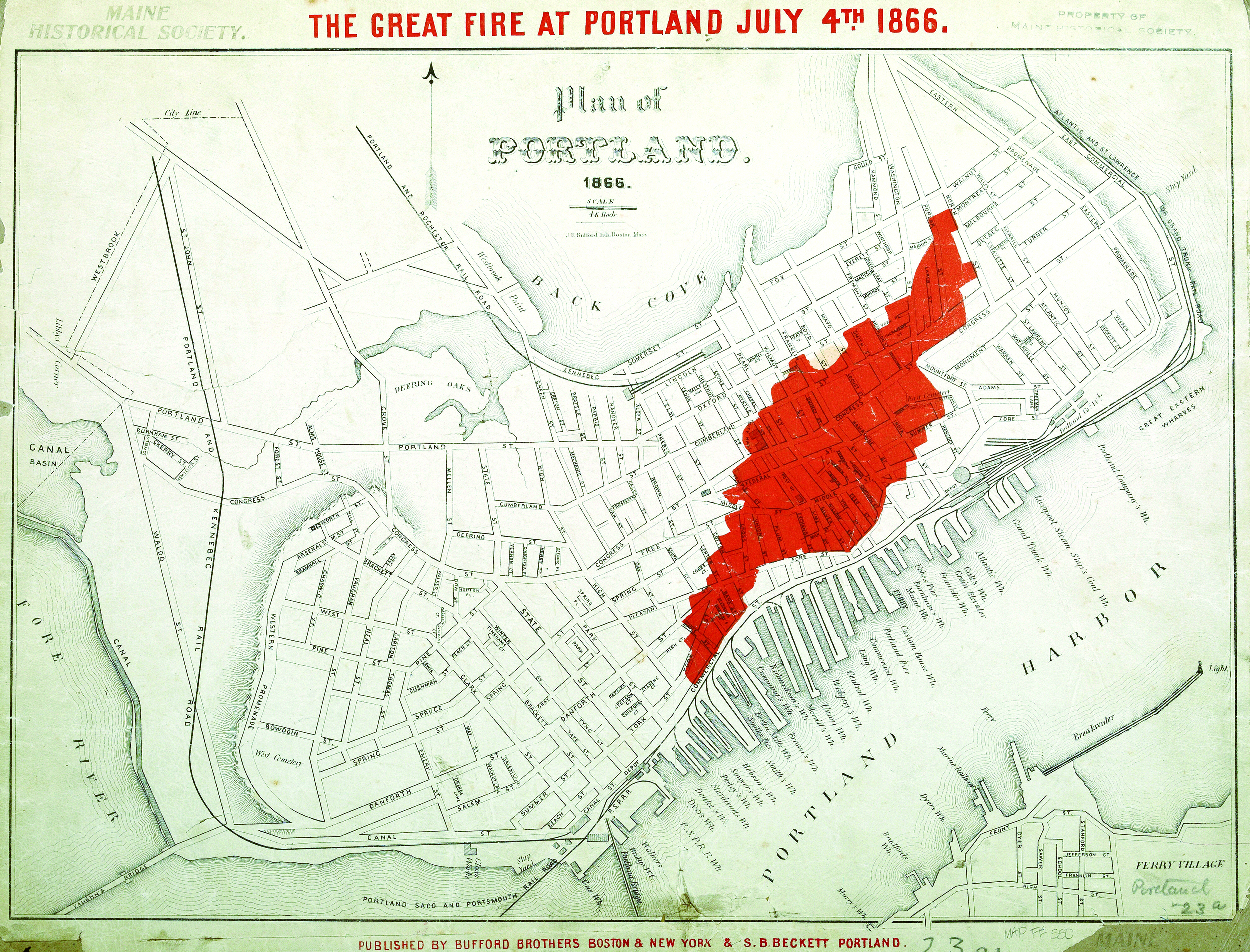

Portland's Great Fire of 1866

Image from Maine Historical Society.

The fire began on the afternoon of July 4th, 1866 as Portlanders celebrated Independence Day. Accidentally ignited, the fire was likely started by a firecracker or a cigar. It began on Commercial Street near the present-day location of Hobson’s Landing (until it closed in 2016, the Rufus Deering Lumber Yard) and spread to John Bundy Brown’s sugarhouse on Maple Street.

The intense heat of the fire melted the building's steel shutters and galvanized iron roof, sending out a thick black smoke over the city. Powered by strong winds, the fire swept diagonally across the city through the Old Port and the India Street neighborhood to Munjoy Hill where, aided by the tireless efforts of the City's firefighters, it burned itself out early on July 5th. Portland’s Great Fire predated the Great Chicago Fire and at the time was the largest fire ever in an American city.

The fire destroyed the new City Hall, the Customs House, the Post Office, all the city's banks, and many hotels, shops, and offices. Several churches were destroyed by the flames, including the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception, which was still under construction. Of the 1,800 buildings destroyed by the fire, 1,200 were residences. These were home to 10,000 of Portland's citizens, leaving both wealthy and poor homeless.

Photographs by J.P. Soule, taken on July 12-14, 1866

In the Aftermath, Relief for Portland's Sufferers

Portland's leaders issued a call for help. The Federal Government shipped 1,500 tents to the city, which were set up in a makeshift tent city below the Portland Observatory on Munjoy Hill. The City of Boston sent five train cars of food that was served from a soup kitchen set up in the old City Hall in Monument Square. Train loads of blankets, clothing and other goods arrived from Sherbrooke, Montreal, and Ottawa in Canada, and from other New England states. As word spread of the extents of the disaster, donations arrived from all over the United States. Letters acknowledging many of these donations were saved by the city and are now available online at the Portland Public Library.

Like a Phoenix the City Arises from the Ashes

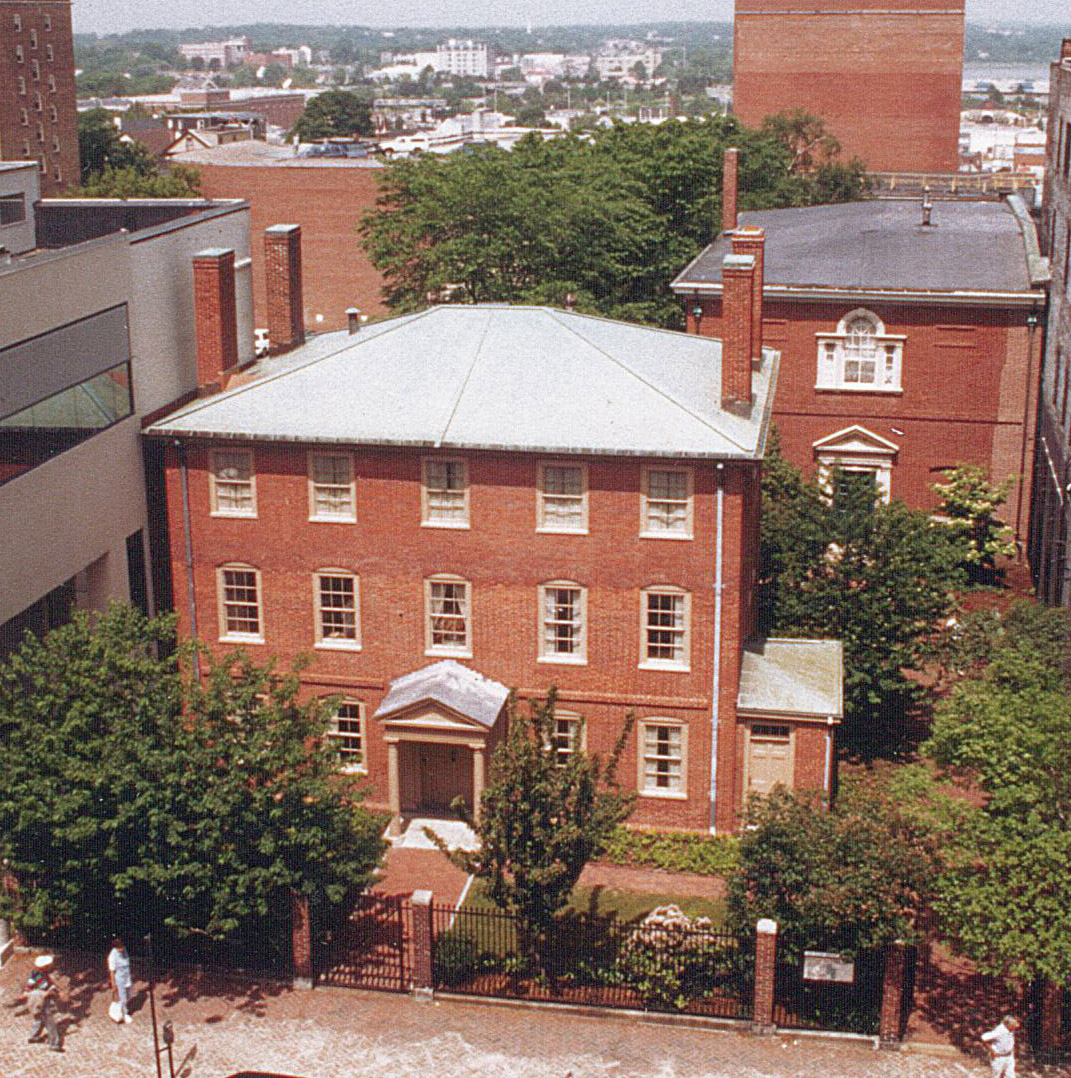

Portland was almost completely rebuilt in the following two years, giving the city its characteristic brick, Victorian architecture. Workers poured in to assist in clearing the debris and rebuilding the city. Architects from Boston, New York, and Canada opened offices in Portland to assist in rebuilding efforts. Most of the buildings constructed after the fire were built in one of the two popular styles of the time period: the Italianate Style and the closely related Second Empire Style. Most commercial and multi-family buildings were built of brick and granite, to lessen the chance of fire. The Old Port was rebuilt as a mostly commercial area, while new residential construction occurred on Munjoy Hill and in new suburbs in Deering. To serve as a fire break between the new commercial area and new residential construction on Munjoy Hill, the city purchased the land bounded by Pearl, Franklin, Federal, and Congress Street for a city park. First named Phoenix Park, it was renamed the following year as Lincoln Park.

To ensure a reliable water supply, the Portland Water Company, later known as the Portland Water District, began piping water into the city from Sebago Lake in 1869. A large reservoir on Bramhall Hill was constructed for water storage in 1868, with a second large reservoir built on Munjoy Hill in 1888. In the neighborhoods affected by the fire, new fire stations were built, like the one on India Street in 1868.

Learn more about the buildings that survived the Great Fire.

Learn more about Portland’s Great Fire:

Portland's Greatest Conflagration: The 1866 Fire Disaster by Michael Daicy and Don Whitney

The Night the Sky Turned Red: The Story of the Great Portland Maine Fire of July 4th 1866, as Told by Those That Lived Through It by Allan M. Levinsky and Earle G. Shettleworth, Jr

The Day Portland Burned: July 4, 1866, an anniversary edition of the Evening Express by Earle G. Shettleworth, Jr.

Account of the Great Conflagration by John Neal