Flooding in Gardiner in 1936 Fogler Library, University of Maine

Downtown Gardiner Floods in 1987 Portland Press Herald

Flooding in a watery state like Maine is not unusual. Spring thaw usually brings warnings of flooding along Maine’s rivers and streams. An occasional Nor’Easter that arrives during high tide can mean flooding will wreck havoc on our coastal communities. What can we learn from past events? What can we learn from other coastal communities across the county? What happens to historic buildings that flood periodically? What can be done to alleviate the repeated flooding and damage to properties? As sea levels rise and storm intensity and frequency increase, preservationists are grappling with these issues. What should we do?

Doing Nothing

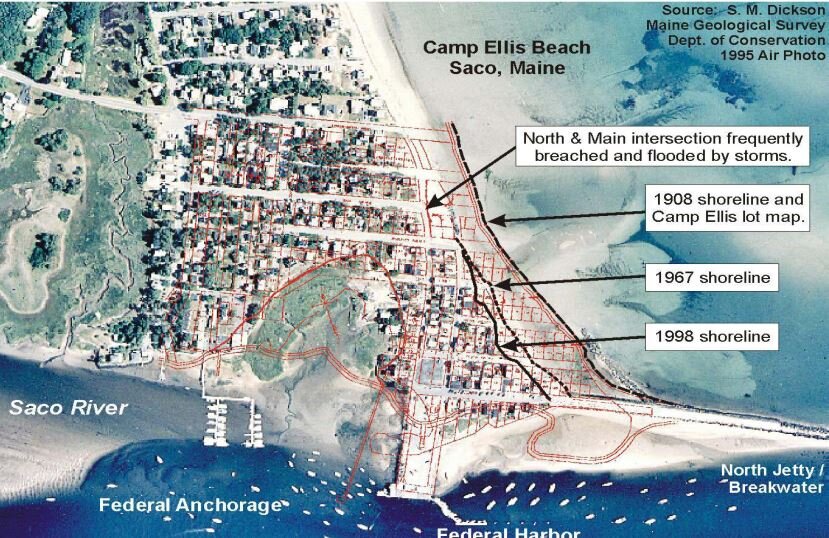

Doing nothing will likely result in the loss of historic resources. Maine has already experienced loss of coastal structures, notably thirty-eight homes at Saco’s Camp Ellis and the dramatic loss of an industrial building in Lubec.

Despite a fundraising campaign and plans to raise and relocate an endangered waterfront building, Lubec lost the historic landmark in a January 2018 storm that lashed the region with snow, rain and high winds. The storm coincided with an astronomically high tide. Listed on the National Registered of Historic Places, the McCurdy Smokehouse brining shed, was located in the channel east of Water Street and long a part of the Lubec Landmarks collection. It came free of supporting pilings during the peak of the storm‑surge driven tide, turning the shed from a historical structure into a hazard to navigation. After crossing the Lubec Channel into Canada, the shed ended up coming to rest on the Campobello shore, where scavengers dismantled parts of it before Lubec Landmarks and Canadian authorities could act. Thankfully, in its float across the channel it did not collide with the Franklin D. Roosevelt Memorial Bridge. More information on the McCurdy Smokehouse can be found at the Island Institute.

Recognize Loss: let nature takes its course

Rising seas and erosion poses an especially acute problem for managing cultural resources because our resources are unique and irreplaceable — once lost, they are lost forever. If moved or altered, they lose aspects of their significance and meaning. Every year, we lose irreplaceable parts of our collective cultural heritage, sometimes before we even know they exist. Therefore, the decisions we make and the priorities we set today will determine the effectiveness of our stewardship of cultural resources in the coming decades.

Economic or other practicalities may mean some communities will decide that they can’t save all their historic resources, either through relocation or adaptation. What then can be done in the short term to manage those properties? Documenting historic resources is always a good first step, then decisions can be made about short term actions.

““Responsible stewardship requires making choices that promote

resilience and taking sustainable management actions. Funding

temporary repairs for resources that cannot, because of their

location or fragility, be saved for the long term, demands

careful thought. Managers should consider choices such as

documenting some resources and allowing them to fall into

ruin rather than rebuilding after major storms.””

The United Kingdom’s National Trust stewards 775 miles of dramatic, diverse and ever-changing coastline around England, Wales and Northern Ireland. With over 700 properties that could be lost due to erosion by 2030 and 247,000 residences and businesses at risk from flooding, in 2005 the organization concluded that they could no longer rely solely on building their way out of trouble on the coast and that coastal ‘defence’ as the only response to managing coastal change looked increasingly less plausible. They established a new policy, Shifting Sands, committing them to working with natural processes and adapting to coastal change – for instance by rolling back, moving buildings and infrastructure out of harm’s way. Their policy sets out goals to:

Be driven by long-term sustainable plans, not short-term engineered defenses

See coastal adaptation as a positive force for good

Take action now – move from saying to doing

Work closely with communities – with everyone having their say

Act across boundaries – join forces with partners and people

Innovate – have the courage to try out new ideas

Aspire to a healthy coastline, shaped by natural forces.

Managed Retreat

Managed retreat or managed realignment is a coastal management strategy that allows a shoreline to move inland, instead of attempting to hold the line with engineered defenses. In many cases of managed retreat, buildings and infrastructure are “moved” out of harm’s way and natural areas are restored in the abandoned area. The restored natural coastal habitat provides extra protection or a buffer from flooding. This approach is relatively new but is gaining traction among coastal policy makers and managers in the face of increased coastal hazard risks. There is a growing recognition that attempting to “hold the line” in many communities is a losing battle - and a costly one.

For decades, federal policy has subsidized building in the flood zone via the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) of 1968. This facilitates a cycle of destroy-rebuild-repeat within the flood zone. Federal data shows that from 1978 to 2018, more than 36,000 NFIP-insured properties filed repeated claims for flood damage. A 2019 study published in Science Magazine laid out a case for strategic and managed retreat, found that a single home in Mississippi was rebuilt 34 times in 32 years using $663,000 in federal tax dollars—for a home worth only $69,000.

Retreat isn’t a word one normally associated with the U.S. military, but Naval Station Norfolk, because of its strategic importance and its vulnerability to climate change, is at the leading edge of adaptation and managed retreat discussions in the country. Naval Station Norfolk is a vast complex in southeastern Virginia whose 80,000 active-duty personnel make it the largest naval base on earth by population. The ships and aircraft stationed at Naval Station Norfolk are at risk as the seas are rising, and the soil is sinking. Already, key access roads to the low-lying Naval Station Norfolk are occasionally submerged during high tides. Current and former Navy leaders have been outspoken on the need to adapt to the increased numbers of days that they experience recurrent flooding and the critical need to make plans for what the Navy will do if Norfolk goes underwater. While headway has been made, planned critical safety upgrades at the naval station were halted and funds redirected by the previous administration.

Back in 2014, the federal government launched the Hampton Roads Sea Level Rise Preparedness and Resilience Intergovernmental Pilot Project (IPP). Its purpose was to bring together civilian and military officials to plan for a future of rising water and worsening floods. For the next two years, city leaders and state planners, Air Force colonels and Navy commanders worked across their own jurisdictional boundaries. They examined how rising sea levels could endanger roads, bridges, schools, businesses, and public health. Despite challenges, it helped change the conversation in the community. In 2019 the Navy and the cities of Norfolk and Virginia Beach released a joint report that looked at steps needed to protect schools, roads, a hospital, and Naval Station Norfolk from the encroaching water. Now Norfolk and Virginia Beach are taking steps to plan and execute relocation of residents in harms way.

Portland’s waterfront and the Bayside neighborhood are already experiencing recurrent flooding and are predicted to increasingly be impacted by the effects of sea level rise. Natural Resource Council of Maine

As Greater Portland begins to plan how to address the impacts of climate change and preservationists assist in those conversations, hopefully we will look at the work being done in other communities here in the United States and abroad that are leading the way in mitigation and adaptation actions that will help to conserve our collective cultural heritage.

Landmarks has been studying the risks to historic properties in Greater Portland and documenting properties that may be impacted by recurrent flooding and sea level rise. We have compiled a guide for property owners to help them begin to think about their property’s risks and potential ways to adapt or mitigate the potential impacts of climate change. You can check out our new publication on our website!