By Julie Larry

Demolition!

Greater Portland Landmarks emerged as an organization in response to the demolition of Union Station (1888) in August 1961. The train station, beloved by people throughout the community, was immediately replaced by a strip shopping center. Edith Sills, civic leader and wife of the former president of Bowdoin College, gathered concerned citizens in her Vaughan Street living room in 1962 to form an organization to advocate for the preservation of Portland’s historic architecture. Among those present was Deering High School student Earle G. Shettleworth, Jr., who later became the director of the Maine Historic Preservation Commission. In 1964, Greater Portland Landmarks was incorporated, with John Calvin Stevens II (grandson of acclaimed Portland architect John Calvin Stevens) as President. While the loss of the train station was a rallying cry to those who wished to preserve Portland’s identity, it was not the only demolition that caused an outcry.

The only remaining building in the former Vine-Deer-Chatham (VDC) neighborhood is the former Curtis Chewing Gum Factory, now HUB furniture.

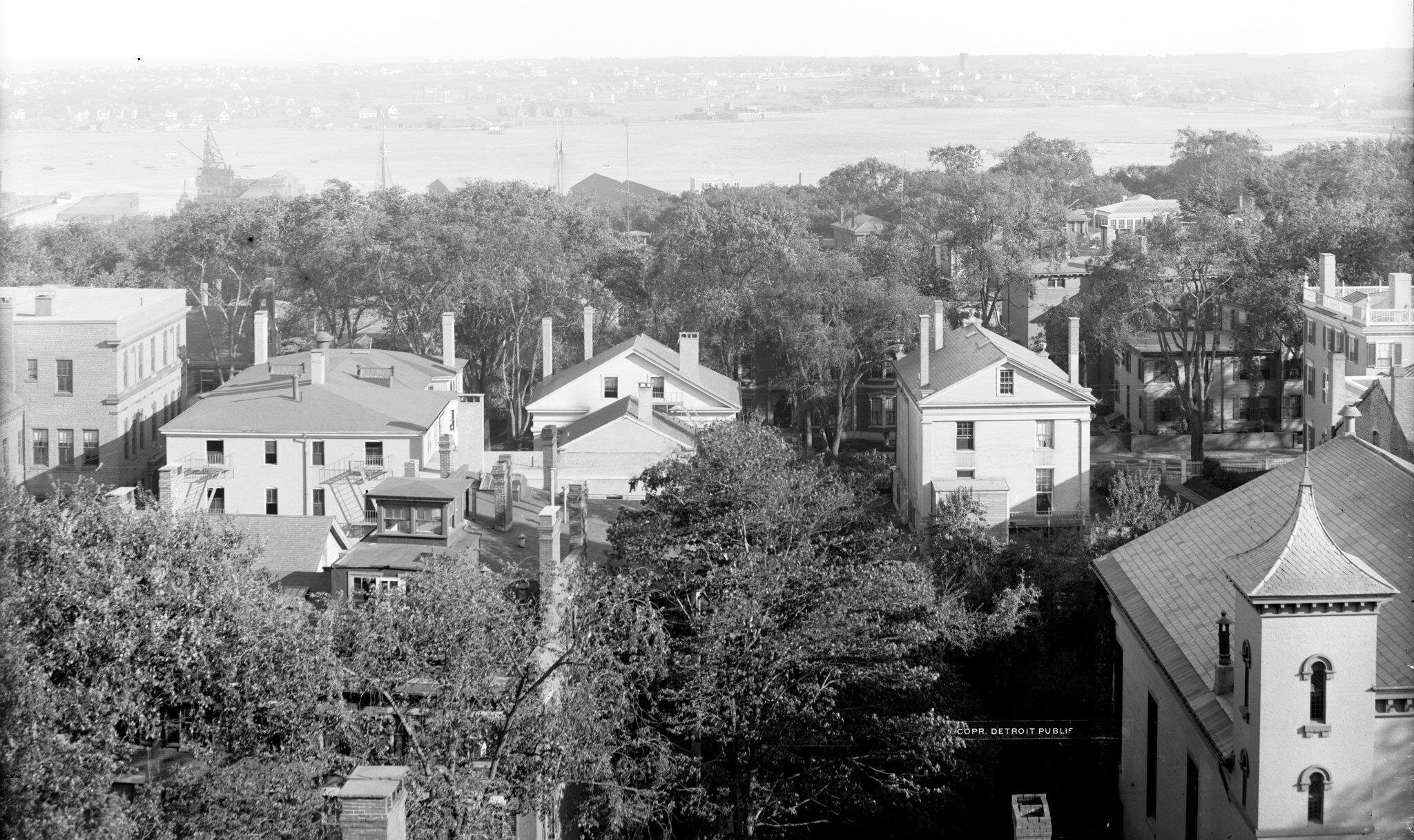

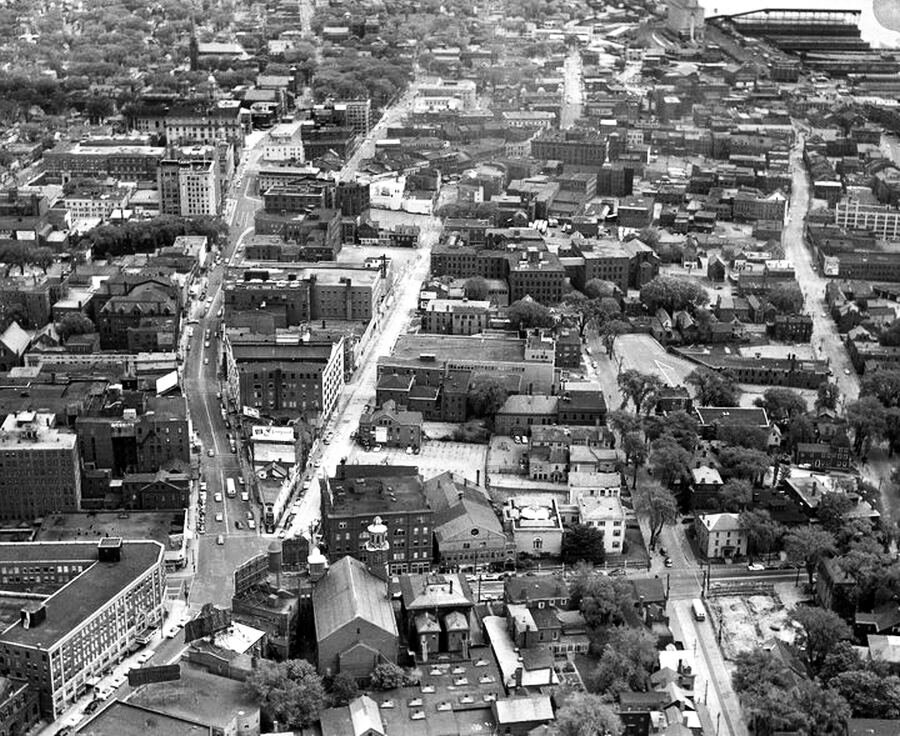

1951 saw the creation of the Slum Clearance and Redevelopment Authority in Portland, but city officials had started thinking about “the problem of the central city” much earlier. In a report published by the Portland City Planning Board in 1946, planners struck a patriotic note when they asked, “Will those who sent their sons out to fight a war on foreign shores approach the achievement of a better and more spacious way of living at home, as fearlessly as their sons did abroad?” Today’s India Street neighborhood abutted two other neighborhoods that were slated for clearance and redevelopment in the post-war years: the Vine-Deer-Chatham area (between Middle and Fore Streets, bounded by Franklin and Pearl Streets) and Munjoy South (northeast side of Mountfort Street). Half the population of Vine-Deer-Chatham, like the India Street neighborhood, was Italian, either foreign-born or first generation. Other residents included Russian-born Jews and Armenians. Residents did not take kindly to their neighborhood being called a “slum” and rejected plans for their removal. The neighborhood was popular with immigrant families as there was acceptance for members of minority groups and, as in other neighborhoods, there were no landlord restrictions against large families.

In 1955 this project was the first in Portland’s slum clearance and redevelopment program. The 6-acre parcel displaced 100 families and 25 commercial establishments. The one building exempt from the clearance was the former Curtis & Son Chewing Gum factory on Fore Street. Initially properties were acquired by negotiation rather than condemnation, and relocation assistance was provided to families. After 18 months, the remaining six properties were taken by condemnation. By 1961, Fore Street was realigned to create a larger development parcel to the north and Jordan’s Meats factory occupied the block bounded by Fore, Middle, India, and Franklin Streets.

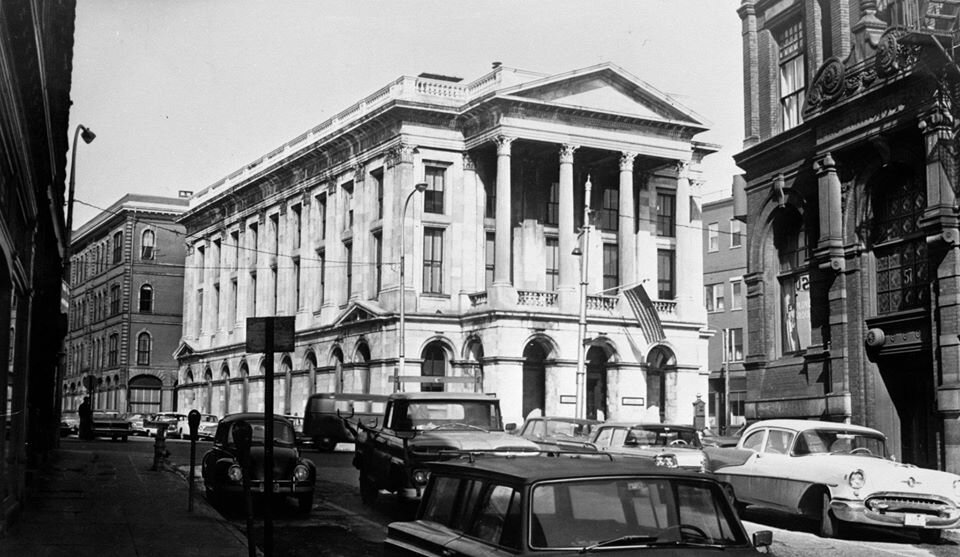

The U.S. Post Office and Courthouse (1868) at the corner of Middle and Exchange Street. Torn down in 1965 for a parking lot, it is now Post Office Park.

The Falmouth Hotel (1868), formerly at the corner of Middle Street and Union Street.

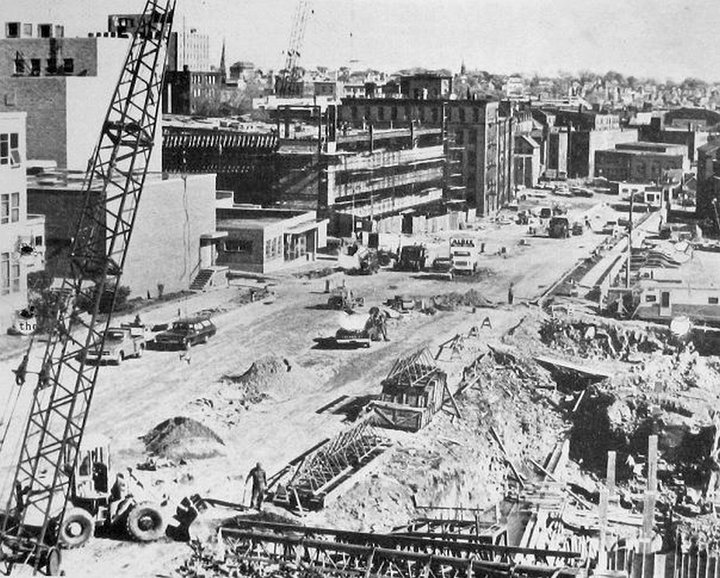

In the 1960s and early 1970s, Urban Renewal was in full swing in Portland. Across the country urban renewal programs encouraged large-scale demolition and reconfiguration of urban areas to accommodate “modern” development, high capacity traffic corridors, and parking lots and garages for the automobile. While some projects in Portland were undertaken by the City’s renewal authority, other demolitions were completed by private owners. Many historic buildings fell to the wrecking ball - the Falmouth Hotel (left), the Old Post Office (left), and the Grand Trunk Railroad Terminal (below) to name a few. Many of the demolition sites were used as parking lots until they could be redeveloped (below).

Cars park on the cleared lot once occupied by the Falmouth Hotel in the early 1970s. Collection of Greater Portland Landmarks

Grand Trunk Railroad Station (1903) demolition in 1966.

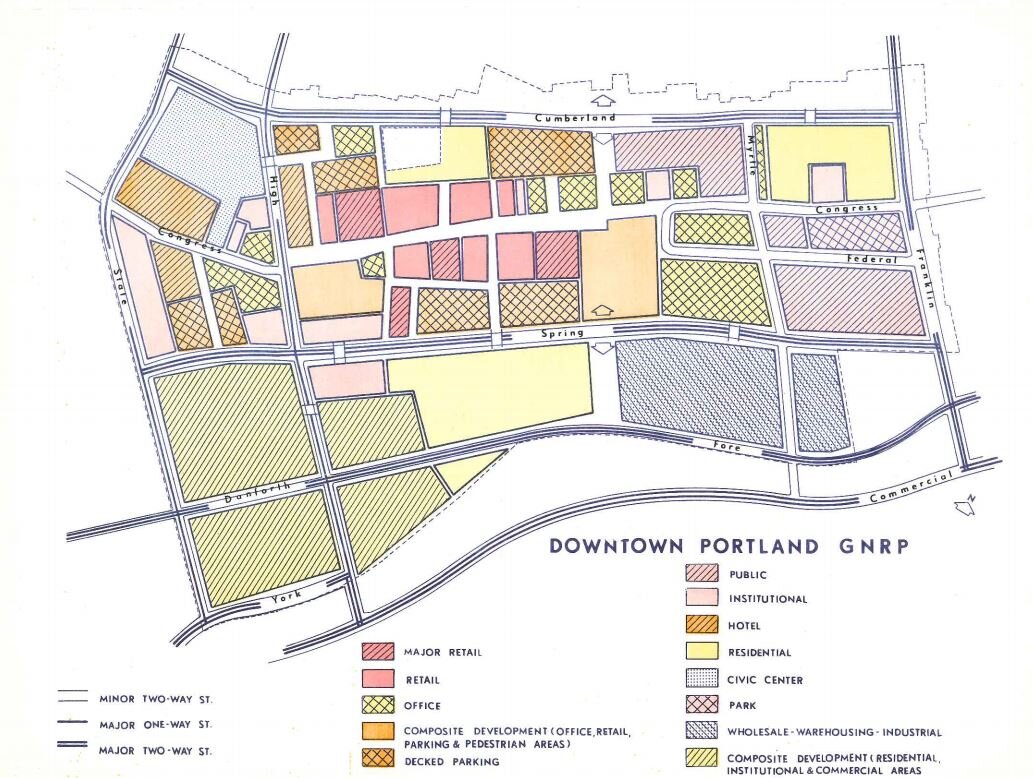

In 1965, on the heels of the publication of his book The Heart of Our Cities, The Urban Crisis: Diagnosis and Cure, architect and planner Victor Gruen was hired by the city leaders to develop a downtown renewal plan, Patterns for Progress, which was published in 1967. The report advocated for clearing numerous areas and redevelopment of the downtown with large office buildings and parking garages as well as a new traffic circulation system with an arterial on Spring Street connecting to a new arterial on Franklin Street. This Urban Renewal plan would have a remarkable impact on the landscape of the city and, along with Union Station’s demolition, was the impetus for the city’s preservation movement.

Collection of Greater Portland Landmarks

Numerous residential and commercial buildings across the city, particularly along the newly planned arterial corridors, were recommended to be removed. The fledgling Landmarks began surveying the city’s historic architecture in 1965 to identify the buildings that should be saved and then set out to save as many as possible. The passage of the National Historic Preservation Act in 1966 helped Landmarks slow some demolitions. Landmarks sought designation of historic districts on the newly-formed National Register of Historic Places to raise awareness and influence development projects in historic neighborhoods.

The strategy worked. Many neighborhoods and buildings, including the Old Port, were listed on the National Register of Historic Places in the 1970s. Landmarks saved the Park Street Row and several blocks of historic buildings from destruction on the west end of the city. The city had to stop the Spring Street arterial at the corner of High and Spring Streets because the newly-designated Spring Street Historic District would be adversely impacted by the federally-funded transportation project. Despite theses successes, swaths of buildings were cleared to make way for the Franklin Street and Spring Street arterials.

Spring Street Arterial

The Spring Street Arterial is a half-mile long stretch of highway in the middle of the City. Historically Spring Street did not extend to Union Street as it does today. The arterial construction necessitated the removal of numerous historic resources. Spring Street was extended from Center to Union, and Middle Street was discontinued between Monument Square and Temple Street. Spring Street’s expansion eastward to Franklin Arterial was stopped by preservationists and allies where the intersection of Union and Temple Streets was realigned. Landmarks played an active role in halting the arterial’s expansion in the Old Port and westward to State Street.

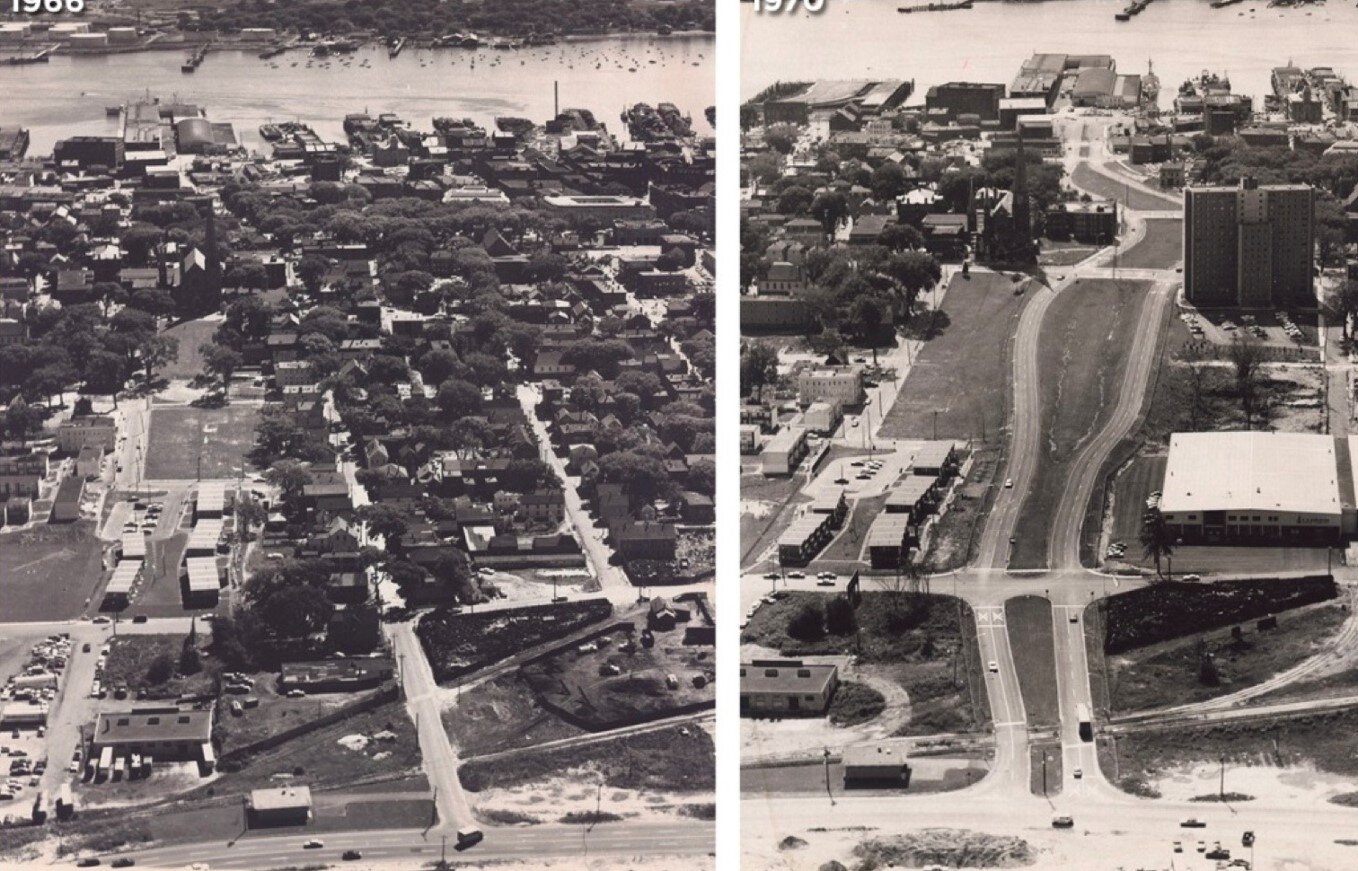

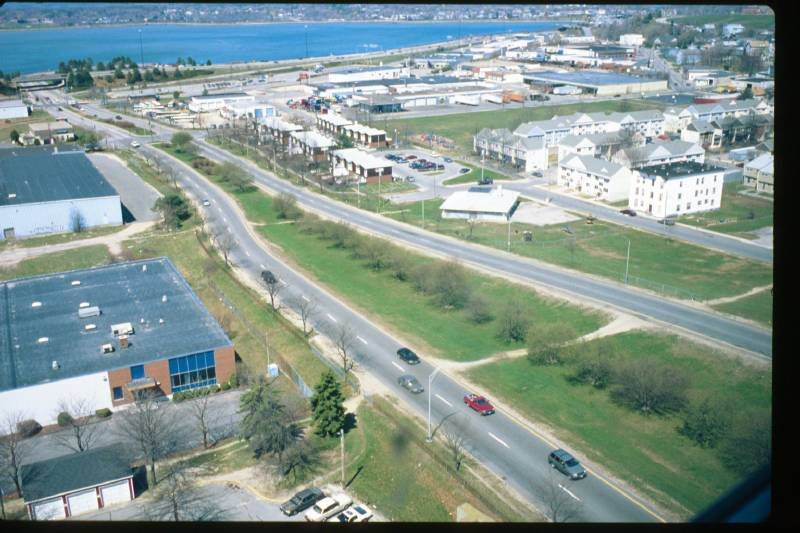

Franklin Arterial

Several of the urban renewal projects disproportionally affected immigrant and minority residents, fragmenting their tight knit communities. This was particularly true with the Franklin Arterial. Franklin Street began in the 18th century as Essex Street, running from Back (now Congress) Street to Tyng’s Wharf at Fore Street. It was later extended to the new Commercial Street and Back Cove when those areas were filled in the 19th century. In the early 20th century, the neighborhoods around Franklin became a dense, mixed-use neighborhood of Jewish and Italian immigrants. In 1958, Portland's Slum Clearance and Redevelopment Administration demolished the mixed‐use area between Lancaster, Pearl, Somerset, and Franklin Streets in a phase of "slum clearance” making way for the “Bayside West” project. The area demolished included 44 housing units, at least 31 households, and was home to more than 85 residents. Across Franklin Street another 54 units were razed for the "Bayside Park" urban renewal project. This area, now called "Kennedy Park,” had through streets that were truncated in an attempt to limit access to outside traffic. The razing of the old Franklin Street began in 1967. 100 structures were demolished and an unknown number of families re‐located. The prominent 16- story residential building beside the arterial is Franklin Tower, designed by John Leasure and built in 1969.

Lincoln Park

Lincoln Park is Portland's oldest public park. It was designed by Portland's civil engineer Charles Goodell and was strategically planned as a protective fire-break between the commercial downtown and residential east end in reaction to the Great Fire of 1866. Lincoln Park served as the green space for a densely populated neighborhood at the base of Munjoy Hill and a place of respite for downtown workers. The construction of Franklin Arterial appropriated the eastern third of the park. Bounded by Congress, Pearl, Federal, and Franklin Streets, the park was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1989 for its significance in landscape architecture. It is also recognized as a local Portland Historic Landscape District.

“The Golden Triangle” - Middle Street

In 1970, the area known as the Golden Triangle between Middle, Temple and Federal Streets was cleared for redevelopment. While plans for a new library or park were considered, the lot at a critical connection between the Downtown and Old Port was used for more than a decade as a parking lot for 160 cars. In 1982 the city put out a request for development proposals and in 1984, One City Center was constructed.

After some success at stopping the demolition of buildings in the West End and Old Port for the extension of the Spring Street Arterial westward to State Street and eastward to Franklin Arterial, in 1975 Landmarks began to focus its political energy on establishing a local historic preservation ordinance. An early effort failed to gain approval in 1978, but the battle continued until the City Council passed the ordinance in 1990.

Congress Square

The one-way traffic pattern of High Street was completed as a recommendation of the City’s arterial traffic plan. Congress Square Park was created in 1982 with an urban development grant from the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development. The goal was to make a showplace for the city and add to the vitality of the area with a new open space opposite the city’s newly expanded art museum. In 1976 plans began for an addition to the Portland Museum of Art’s L.D.M. Sweat Memorial Galleries. The new addition necessitated the removal of several buildings, the largest of which was the Libby Building (1898-1981). The Libby Building was built for the Y.M.C.A in 1898 on the former site of the Cobb/Cahoon/Libby mansion. The new museum building, designed by I.M. Pei & Partners, opened in 1983.

The Tracey Causer Block on Fore Street in 1991.

During the 1980s, development pressures increased as Portland became part of the New England real estate boom. It was a race to try to save buildings like the John B. Carroll Block (1857) and the Tracy-Causer Building (1866). Some attempts were successful, many were not. In June 1988, Citizens rallied in front of bulldozers and risked arrest at the site of the Carroll block on Park Street when it was demolished in anticipation of the new preservation ordinance that could have saved it. While Landmarks’ efforts to build awareness about preservation were paying off, the loss of this Italianate duplex demonstrated that more work was needed.

The Tracy-Causer Building on Fore Street was slated for demolition to clear a development site. This building stood just outside the newly proposed historic district. It was vital to save one of the last surviving Greek Revival commercial buildings in an area that had lost much of its character to real estate speculation. Landmarks advocated for a demolition delay ordinance, approved in 1989, which saved the building. The individually landmarked Tracy-Causer Building is now a vital part of connecting the Old Port area to the Gorham’s Corner neighborhood. The parking lots to the east of the block may finally be developed decades after they were first cleared for redevelopment.

While this blog post focuses mainly on Portland’s downtown, other areas of the city were also cleared for redevelopment, particularly residential areas in Bayside and Munjoy Hill. Urban renewal activity between 1961 and 1972 destroyed approximately 2,800 units of housing (Bayside alone lost over 1,100 units of housing), housing units that today the city is struggling to replace. A little more than 525 units were created in new housing developments during the same period. We’ll leave those stories for another day, in the meantime, a few more photos:

Special thanks to the Portland Maine History 1786 to the Present Facebook group. Without their wonderful collection of Portland images it would be difficult in this time, when we have limited access to our own photographic files, to have completed this blog. Thank you too to all the individuals that contribute images and their memories of Portland in the past to the group, particularly the family of Dr. Henry Pollard. Many of his aerial images of Portland in the 1970s are featured in this blog. If you aren’t following their Facebook page, you should! - Julie