As many of Portland's historic districts and buildings are located in District One and District Two, we know you are interested in learning more about the candidates in this year's City Council elections. We asked all eight of the Portland City Council candidates to answer a quick survey about preservation issues our supporters are concerned about, mainly affordable housing, climate change, and economic development. Candidates Roberto Rodriguez (At-large) and Anna Trevorrow (District 1) did not respond.

Greater Portland Landmarks does not endorse candidates, but we do like to help our supporters be informed of candidates' positions. We hope that you will find the following information helpful as you cast your ballots in the upcoming municipal election.

Question 1: What is your favorite historic place in Portland? Why?

Sarah Michniewicz (District 1): The Old Port makes me feel steeped in Portland's past, particularly any street with cobblestones, and most especially the working waterfront. But it's the interiors of historic buildings that make me feel the most connected to Portland's history. From detailed moldings to a single handcut nail, human energy is infused in the places that make Portland historically relevant and special.

Jon Hinck (District 2): The Abyssinian Meeting House. The building is elegant in its simplicity. But the Abyssinian Meeting House speaks to those who pay attention because of its history. It is also a special landmark because the building stands only because of community activism, philanthropy and care. Plus it needs more of our attention.

Victoria Pelletier (District 2): My favorite historic place in Portland would have to be the Abyssinian Meeting House. As we all know, it's the oldest standing African American Meeting House in the United States, and despite a lot of untold history of African Americans in this country, it's an important landmark that I'm proud to have in this city, and a starting point of conversation about Black history, specifically in Maine.

Travis Curran (At-Large): The Portland Observatory, it's always been present in my neighborhood and when I was a tour guide it was my favorite destination to recommend to visitors. The unique history of the building appeals to me as well as the in-depth tour with each floor presenting new and different information, culminating at the top with the breathtaking view of the city. I try to go up at least twice a summer.

Brandon Mazer (At-Large): Longfellow House--I have always had a fond appreciation for Longfellow and it is one of the places I always take visitors from out of state when they visit Portland. During high school (in Iowa), it was always with great pride when we would cover him in English class.

Stuart Tisdale (At-Large): Stroudwater. I used to live on outer Westbrook Street and I would drive through past the "Established in 1643" sign at least twice a day. I loved the sense of history that gave me, a high school history teacher. Also, there is a white clapboard house on the north side of Westbrook Street, just up from the corner of Congress. The house is three-stories with a barn-like shape. I read that the house was a way station on the Underground Railroad and has, or had, secret compartments to conceal runaway slaves. I am using that house in a novel I am writing about five abolitionist brothers from Portland who journey to Charles Town, West Virginia, in November 1859, to try to break John Brown out of jail.

Question 2: There is a significant correlation between affordable housing and historic buildings in Portland. Much of Portland’s existing reasonably affordable rental housing stock is found within the historic building fabric of the peninsula neighborhoods. In Portland’s historic buildings and districts, more than 900 new housing units have been approved and more than 400 completed in the last six years. Nearly 75% of those new units are affordable for low-income residents and seniors. What incentives would you support to promote the preservation and creation of affordable housing in conjunction with rehabilitating historic buildings and neighborhoods?

Sarah Michniewicz (District 1): The City recently agreed to further study historic districts and their relationship to affordable housing, and I fully support this effort. I would like to see rehabilitation programs like the New Neighbors program in the 90’s revitalize housing stock in order to both preserve existing an historical buildings and ensure a wide variety of housing types are available to a wide range of income levels in all neighborhoods, particularly on the peninsula. I also strongly support adaptive reuse of existing structures, such as has been done on the former public works site. Finding creative strategies to support and maintain our historic structures is part of how we can develop and enliven the city without losing touch with our past.

Jon Hinck (District 2): I would support: the creation of a universal safety net voucher program for those who want to live in historic as well as other neighborhoods; the creation of incentives generated from housing linkage fees on large commercial developments to support building affordable housing; and elimination of structural barriers that minority households face when seeking home ownership.

Victoria Pelletier (District 2): We need a full comprehensive review of our city zoning laws, which work to prohibit affordable housing, along with the data of the current income and wealth gap between people of color and white individuals in Portland. The current single-family zoning we have in place in Portland promotes city-wide segregation and makes housing less affordable for all. We have a wonderfully diverse district filled with low to moderate-income, working-class individuals like myself, and if we’re not discussing zoning laws, Airbnb’s, and other short-term rentals, we’re just upholding systemic barriers and actively driving our young people and seniors out of the city because they can’t afford to live here. In order to continue investment into the economy, we need to retain young people in Portland, and if we don’t work to prioritize their quality of life over appealing to tourists, then we cannot accurately say that Portland is a city for everyone. It’s important that all District 2 neighborhoods advocate for housing for all, especially those who are in higher quality living quarters, because if we can push to end exclusionary zoning laws, it’s the first step towards not just saying ‘housing is a human right’, but advocating for it with policy.

Travis Curran (At-Large): Enforcing the AirBnB regulations and non-owner occupied cap to free up already existing affordable units, for there are plenty of illegal AirBnB's skating by with little repercussions whatsoever. Portland's history is very important, but the housing crisis is worse than ever, so I'm pushing for rezoning the outer districts to eliminate single-family-unit only zones, allowing for more apartment buildings and mixed-use zones along our major corridors.

Brandon Mazer (At-Large): I believe we need to start focusing off peninsula to encourage more dense affordable housing. Much of these areas are not in current historic districts; however, a few are. We need to make it as easy as possible for those that are creating affordable housing to do so as efficiently as possible and provide any subsidies and grants to help offset some of the higher costs of rehabilitating historic buildings.

Stuart Tisdale (At-Large): I am not a builder, so I do not know the technical names of incentives; but, as a history teacher, I am inherently sympathetic to preservation efforts. I am also keenly aware of the affordable housing shortage in Portland, and not only for low-income people but also for those of moderate income. So, if historic preservation could be linked with affordable housing, then that would be a win-win situation, and I would support the creative use of incentives to achieve that goal. I would not permit developers to buy their way out of including affordable housing in their development projects.

Question 3: Historic (and non-historic) buildings in low lying and waterfront neighborhoods are at risk of– or are already experiencing – the damaging effects of sea level rise. How can the City address climate change while maintaining our critical historic places? What can the City do to assist Portland residents and businesses coping with sea level rise impacts?

Sarah Michniewicz (District 1): Slowing climate change is all of our responsibility. Historic and older buildings can contribute through robust weatherization measures that reduce the consumption of fossil fuels and historic preservation standard that allow for visually appropriate and energy efficient window and heating and cooling systems. The City should continue to educate and support weatherization programs, particularly for senior and low-income residents. Mitigating climate change is particularly important for historic buildings in low-lying areas of the City that are prone to flooding. Vulnerable areas in the Bayside and East Bayside neighborhoods need to be protected. A great deal of work has been done to evaluate and potential impact, from the 2009 Sustainable Portland Update through the 2017 Portland Comprehensive Plan update, and continued exploration of mitigation strategies like the League of Cities-sponsored Bayside Adapts design challenge is essential. I recently supported a living shoreline climate mitigation study and will continue to support such initiatives.

Jon Hinck (District 2): The City needs to undertake much more aggressive climate mitigation steps including for the protection of historic buildings and blocks. The undertaking presented from rising sea levels and other climate-induced flooding is substantial and unprecedented. Detailed plans for how to counter flooding and heat damage should be generated soon. This will enable Portland to seek funding from national sources particularly those dedicated to preservation. Some of Portland's threatened historic properties are certainly of national interest. We will need to be prepared to raise and contribute money needed for this vital effort.

Victoria Pelletier (District 2): This current climate crisis represents a precipice of culture change for people like me living in Parkside, Portland and all Wabanaki Confederacy Territory, and it's important to lead our community through this tipping point from confusion toward collective action. Mitigating climate change requires collaboration from many intersections; I’ve come to understand the most meaningful actions are embedded in local solutions. I will lead Portland in considering concepts of Equitable Adaptation where members of frontline communities, marginalized folks, and people who rely on environmental resources are encouraged to gather in dynamic practices of inclusive community driven engagement for climate action planning, especially for the waterfront and Bayside areas of Portland. In discussing climate change adaptation and mitigation with the Portland community, I also find that this is an issue that is often led in an overwhelming fashion by white individuals, despite the fact that our vulnerable and marginalized community members will feel the immediate impacts. Due to this, it's really important that in education on climate justice, I make sure to advocate that everyone has a role to play, regardless of the direct connection to emission reduction and green building standards -- it’s important to also intersect this conversation with the preservation of history and cultural significance, especially as Portland continues to diversify. I look forward to using my platform as an advocate to resume my ‘community chats’ I hold on the promenade, to educate Portlanders on the impacts of rising sea levels, climate adaptation, housing quality and affordability.

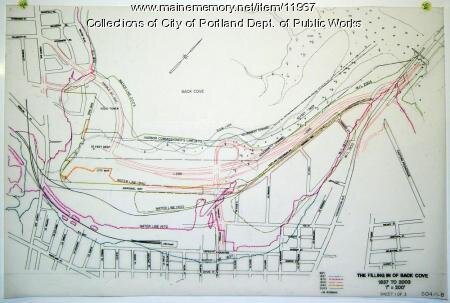

Travis Curran (At-Large): We need to seriously overhaul our infrastructure of the land that is historically landfill by researching safe ways to prevent flooding and studying other coastal cities at risk to see if their methods have been effective for not. The tide's not going to stop rising and we must prepare for that yesterday.

Brandon Mazer (At-Large): For new buildings, we can adjust some of our zoning regulations to allow for more flexibility with height and design to anticipate sea level rise.

Stuart Tisdale (At-Large): Again, I am not a builder or an architect, so I would rely on those professionals to propose ways the City might help cope with sea level rise. Global warming is real, human agency is certain, and Portland's goals of reducing greenhouse gas emissions among the general population and promoting the municipal use of clean renewable energy will do our part in mitigating sea level rise. I declare that I will be sympathetic to any reasonable proposals for what the City might do to assist Portland residents and businesses cope with rising sea levels.

Question 4: Currently there are many buildings in historic neighborhoods that have no protection from demolition and no guidelines for new construction, often resulting in tear-downs and new buildings that are not in scale or in keeping with the neighborhood. Do you have concerns about the loss of historic buildings and/or the design, mass and scale of infill development? How would you address this issue?

Sarah Michniewicz (District 1): Yes, I do worry about the loss of historic buildings, noting that the definition of historic can be subjective. In addition to preserving buildings that are more traditionally considered historic, it’s important to preserve smaller scale existing homes and blocks of homes that both provide affordable options for renters and memorialize Portland’s rich past, particularly in areas where immigrant communities and diverse populations formerly flourished. I have concerns about the definition of neighborhood context in areas where teardowns, both long ago and recent, and the new developments that have replaced them, have already changed that context. What does appropriate infill mean in areas where much of the original neighborhood fabric has already been altered? We need very clear definitions in order to make decisions that reflect our goals for historic preservation, smart growth, and neighborhood development. The design standards being examined in the current Re-Code phase 2 process should be considered carefully. This is an opportunity to make changes that will impact the look, feel, and growth of Portland for years to come. I would strive to support a balance between respecting existing context and encouraging the amount and type of development needed to grow our housing stock, particularly for lower and middle income residents and families.

Jon Hinck (District 2): Yes and Yes. Portland needs to examine extending historic preservation to cover additional historic buildings and zones.

Victoria Pelletier (District 2): The discussion of historic preservation is an interesting one, especially as Portland becomes more racially and ethnically diverse, because this opens up a conversation about whose history we’re working so hard to preserve. At times, ‘historic preservation’ feels synonymous with white centered dominance, and advocating to preserve this ideology feels like we’re not actively making room for the new Portlanders that we claim to welcome and support. The interesting thing about Portland is we celebrate it as a progressive melting pot, but the reality is, there are still many difficult conversations surrounding the impacts of historic preservation. Even the phrase “keeping with the neighborhood” feels white centered and not inclusive. It’s not a secret that our city is segregated - our housing density is in clusters of single-family zoning and short term rentals, that continue to displace working class Portlanders, many of whom are Black people, Indigenous People, and People of Color. It feels inauthentic to call for affordable housing for *all* if we’re also, in the same breath, having discussions about ensuring residents follow specific neighborhood guidelines. Not only does this specifically impact those of us who deal with housing inequities, but it also impacts our small businesses located on the peninsula. The strict guidelines that are put upon new businesses, especially those trying to sustain operations in the midst of a pandemic, act as an unnecessary barrier to economic success. Small businesses and frontline employees are the backbone of Portland, and putting guidelines as to how their businesses need to look, especially when we’re talking about a sign, paint color, or a garage door, undermines the personalization and creative control of the owners, and can have a negative impact on their long-term success. I’m always open to discussions on history, and listening to why and how it should be preserved, but there’s a level of classism that comes with wanting to keep neighborhoods the same while we have a large population of individuals that remain unhoused. I prioritize getting our most under-resourced community members into actual affordable houses, before worrying about a building being out of step with the rest of the neighborhood. Given last summer’s ‘listening and learning’ that came from white allies after the murder of George Floyd, I actually think we have a great opportunity to put an emphasis on inclusive historic preservation and highlighting the intersections between architecture and racial justice. (and, Preserving the Abyssinian House is a great start). I also think this is the crux of why it’s so important to ensure we have diverse perspectives in leadership positions. We need to advocate for shared understanding and open dialogues, while understanding that we each see these topics through different lenses. It’s these important conversations that will aid us in shaping a city that can truly be for all of us.

Travis Curran (At-Large): The Maine Historical Society needs to make important decisions on which buildings to protect and keep and which we can sacrifice for the sake of the others. Density is important to a city's growth but we can strike a balance without losing our historic structures that bolster Portland as a destination city rich with history.

Brandon Mazer (At-Large): We need to have an in-depth review of the design standards to ensure that if and when buildings are demolished that the new buildings that are built in there place are rightfully in the context of the surrounding buildings.

Stuart Tisdale (At-Large): I have always loved the aesthetics of historic streetscapes, like Park Street or the row houses on the corner of Carroll and Thomas Streets. I remember when the City intended to tear down most of the Old Port, but was deterred by Frank Akers and others who saw the value in historic architecture. I remember once, when I was very young, being taken on the train to Boston from Union Station, which was torn down for an Arlen's Department Store and parking lot. One can only imagine the value that old structure would have today if it had been properly preserved. So, yes, I do have concern. The City, no less than private developers, are capable of blindness to the value of historic buildings and to the worth of preserving the scale of historic streetscapes. To the extent that the City Council has veto power over any such projects, I will vote against them absent powerful countervailing considerations.

Question 5: Historically the peninsula and the City’s major transportation corridors were denser than existing conditions and had a greater mix of residential and commercial uses. The automobile, Urban Renewal, and mid 20th century zoning have had a lasting impact on the City – good and bad. The downside is Portland’s early 20th century public transportation network was displaced, parking lots replaced many homes and businesses, and dense historic building patterns and uses were curtailed. Would you support new zoning and land use policies that urge developers to create new well-designed, higher density developments on underutilized lots to reknit the fabric of our neighborhoods and enliven the city’s major corridors?

Sarah Michniewicz (District 1): Yes, I would like to see zoning examined and transportation systems improved in order to take advantage of existing infrastructure and transportation corridors thereby creating new, walkable village centers, particularly off-peninsula. This approach to growing and revitalizing the city is explicitly called for in Portland’s 2030 comprehensive plan. On peninsula the completion of the METRO peninsula loop and continued revitalization of underserved neighborhoods like Bayside with new mixed use developments and inspired adaptive reuse will help grow Portland’s housing stock, and vital neighborhood amenities, and build a more vibrant and connected community. The key word is “well-designed,” so that new development adds new energy while simultaneously harmonizing with the existing context in ways that make sense.

Jon Hinck (District 2): Yes. I am aware of the urban planning concepts outlined in this question. I share the views expressed here and would support the new zoning and land use policies suggested. My current thinking is completely in line with this. I would remain open to learn more and to assess how best to move forward on this important set of priorities.

Victoria Pelletier (District 2): I look forward to a full review of our zoning and land use policies and agree that we need to increase residential density (both on and off peninsula) on traffic corridors. This also opens up an important discussion on the necessity of increased public transit and reduction of parking requirements so that we can advocate for real affordable housing. Portland is a small, efficient, and walkable city. However, it has been morphed into an ideal that fits with the globalized commercial nature of our American culture. Our city has so much potential to be a leader in transportation efficiency, but it first could benefit from championing the characteristics which make the people and the infrastructure great, while denouncing the high carbon flair of the past. Due to this, not only is it important to review zoning and density, but we also need elected leaders that push for policies that will encourage less driving and mode switching, and more options for walkability and public transit.

Travis Curran (At-Large): As I stated above, yes, I will absolutely urge and create incentives for developers to build more affordable workforce housing along our major corridors, paired with smarter public transit, we can create thriving neighborhood centers while still keeping Portland's history and spirit intact.

Brandon Mazer (At-Large): Absolutely. We need to start getting away from having such high parking requirements, especially on major transportation corridors and using this space for housing.

Stuart Tisdale (At-Large): I am sickened by sprawl and strongly favor mixed use neighborhoods with greater density. To me, Deering Center, where I live, is our most successful neighborhood, because it has mixed uses and epitomizes the concept of the walking city. I can walk to the store, to a deli, to a restaurant, to a coffee shop, and to get a haircut, among other things. Kids in the neighborhood can walk to school, to a Friday night high school football or soccer game under the lights, or to the Little League Field. I am all in favor redesigning neighborhoods with a greater mix of residential and commercial uses. If there were more frequent Metro service between the neighborhood and downtown, it would be even better.

Note: Council Candidates Anna Trevorrow (District 1) and Roberto Rodriguez (At-Large) were contacted by email, twice, but did not respond to our survey.

![IMG_0592[1].JPG](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/555c99afe4b027a64d6975df/1628626368088-9RQBLVJ68H0K00AVYN0L/IMG_0592%5B1%5D.JPG)

![IMG_0609[1].JPG](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/555c99afe4b027a64d6975df/1628626016176-BE53GQT40LW14TFJMFIQ/IMG_0609%5B1%5D.JPG)